UberPool Social

An exploration into how designing for social interaction in ride-sharing may build trust and foster a psychologically safe environment.

overview

About the Project

Abstract: As wonderful and convenient the sharing economy is, technology often abstracts away the realization that we are interfacing with human beings. Initially, our project sought to remove the social awkwardness in ride-sharing. Interestingly, we discovered that increased social interactions not only made ride-sharing customers feel more comfortable, but also led to an increase in perceived comfort, trust, and safety. This 2-part case study explores how to establish healthier relationships between people and technology with a focus on solving the ambiguity around the social atmosphere with passengers in UberPools. Most importantly, the byproduct of our solution creates a psychologically safe environment for passengers using conversation.

The Solution: A ride-sharing experience that (1) matches passengers with similarly preferred social atmospheres, (2) prompts social interactions with personalized conversation starters and (3) seeks to build trust with passengers who were initially perceived as strangers.

Timeline: 3 hours (Part 1) + 3 weeks (Part 2)

Team: Perrin, Ismael, Aleksei, Havi, and Me (Part 1) + Ismael and Me (Part 2)

My Role: User Experience Design, Interaction Design, User Research, and Product Thinking

Content Strategy Role: Part 2, the phase wherein the product was designed, was done by a team of two (Ismael and I). As the the Product Designer, the prompts, onboarding introduction, and conversation starter questions—essentially, everything written on the app was written by me. During and after wire-framing the product, I tested the copy with real UberPool users to incorporate their feedback into the design and copy.

Final Pitch Deck

part 1

A Project Inspired From a Designathon

Our team had attended Rehack, the first-ever intercollegiate reverse hackathon, at Princeton University. The hackathon focused on encouraging dialogue in and support the development of creative solutions that allow for more significant and healthier relationships between people and technology.

Using principles in human-computer interaction, humane design, software development, and tech ethics, Rehack urges participants to think deeply about their interactions with technology and redesign consumer tech products in a more meaningful, socially responsible way.

Given the hackathon's strict 3-hour timeframe to execute on a deliverable, our team focused on designing a proposed solution that could quickly and easily be tested-in a low fidelity way-out in the field without any engineering involved.

Our Team

We are a group of 5 design students from Columbia University’s UX Design Lab with diverse backgrounds ranging from computer science, data science, psychology, and venture capital. From left-to-right: Ismael Barry, Aleksei Igumnov, Havi Nguyen, Ji Yeon Kwon, and Perrin Anto Jones.

Presentation, Feedback, and Srikanth Jalasutram

In addition to presenting our project to judges from IDEO and Headstream, we were most excited to walk through our design process and solution with a representative from Uber. We had the honor of presenting our project to Srikanth Jalasutram, who leads the inclusive design & accessibility practice within Uber's design team.

From left-to-right: Srikanth Jalasutram and our team presenting to Srikanth.

Srikanth critiqued our design through user experience, product thinking, and business point of view. Below is the following feedback we received:

If a rider cannot be matched with a person that feels chatty, will they be matched with anyone? Will the platform set expectations for the either of the passengers?

How will our proposition affect the Uber algorithm? Will people have to wait longer to be matched accordingly?

Does this experience improve trust or safety in the car?

How will you incorporate UberPool Social at scale while maintaining safety and trust?

Is the driver part of the experience? Why or why not?

Our Final Deliverable

Below is our project presentation slides documenting our story and solution. We had presented them to the judges and audience.

part 2 - FURTHERING OUR APPROACH

Building on our Redesign

In part 1, we focused on exploring how to reduce the social awkwardness in UberPools by addressing the ambiguity around the social atmosphere. During the qualitative research our team had conducted, by riding in three UberPools, we discovered that passengers were detailing how comfortable, enjoyable, and friendly the UberPool Social experience was. Namely, the byproduct of increased social interaction led to an increased perceived comfort, trust, and safety. However, Srikanth had questioned us heavily on how our solution may scale. Unfortunately, given the strict 3-hour hackathon timeframe, we did not have time to consider this.

We realize that we have a wider responsibility for addressing this concern as it was overlooked. Ismael, one of the members from our team, and I decided to test and scrutinize our initial assumptions, incorporate the Srikanth’s feedback, and to explore how UberPool Social may create a psychologically safe environment for passengers using dialogue.

This process required us to spend most of our efforts in the user research and prototyping phase of the design process. Part 2 dives into investigating the safety climate around ridesharing through exploratory research. Furthermore, we address further decisions to uphold and maintain in order to fit inside Uber's existing ecosystem so that UberPool Social can scale without compromising passenger safety.

About the Ride-sharing Space

When looking at the volume and frequency of ridesharing, even the slightest negative instances can magnify to impact other end users exponentially. Safety has been and continues to be a pressing issue between driver-to-passenger (and vice-versa) and passenger-to-passenger. According to the Uber United States Safety Report of 2019, nearly 4 million Uber trips happen every day in the US-that’s more than 45 rides every second. The following are statistics about Uber cited from Business of App's Uber Revenue and Usage Statistics (2019) and Much Needed's User by the Numbers: Users & Driver Statistics, Demographics, and Fun Facts (2019).

Operates in 83 countries and over 858 cities worldwide.

There are 75 million monthly active riders.

14 million trips are completed each day.

Well over 10 billion trips have been completed worldwide.

The above statistics are staggering as it shows the growth and success of Uber as it has scaled over the past decade. However, unfortunately, the frequency of lawsuits and concerns associated with sexual assault, lack of safety, passenger misconduct, and trust between passengers is just as staggering and continue to plague the company and the Uber community.

How Do We Know This is a Real Problem?

On December 6, 2019, Uber released its safety report, which revealed shocking statistics. BBC, CNN, Vox, New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal headlined and dove into the 3000+ sexual assault incidents that were reported in 2018. Although the details in the report are unfortunate, there have been many cases, in addition to sexual assault, that has surfaced since the inception of Uber. You can explore Uber’s safety reports here.

Examining Steps Uber has Taken

During the last two years, Uber has taken great initiative in addressing the scrutiny with passenger safety in their cars. The byproduct was a series of features. Some of them include the following. Soon a new optional verification system will require a driver to get a PIN code from their rider before a trip can start.

Furthermore, riders can text 911 from inside the app, automatically sending the vehicle description, license plate, current location, and destination. You'll also be able to report safety issues during a ride. Ride Check, also a new feature, flags long, unexpected stops during a route. In such instances, Uber will send notifications to the driver and passenger to check that stop was requested. If there is cause for concern, either the driver or passenger can press an emergency button in the app.

Most interestingly, much of these features tend to be defensive (used after an incident has happened) rather than active (used before an incident has happened). The reality is that safety concerns in Ubers have drastically risen because people have the opportunity to be bad actors without any repercussions. By deciding to take a defensive stance, people will continue to be bad actors-the only difference is that passengers will now have the option to do something after the situation. However, by taking an active stance, there is an opportunity to reframe people’s understanding of how they should conduct themselves in the Uber experience. That is not to say that defensive measures are not helpful, but instead, they should be considered after an active stance has been taken.

AREA OF OPPORTUNITY

Exploring Areas of Opportunities to Improve Safety Further

Uber's current approach to safety was an implementation of features specific to the Uber experience for lone passengers (e.g., UberX, UberBlack, UberXL, etc.). However, no efforts were taken to address safety in their services between multiple passengers (e.g., UberPool). Although Uber has not disclosed any public data or reports regarding safety in UberPool, at such a large scale, safety incidents are bound to happen (and probably have happened). Namely, it’s imperative to act preemptively to address possible safety incidents before any actually happen.

How might we increase not only perceived trust but also safety among passengers in UberPool?

In a sharing economy, we are more interconnected than ever, but our interactions with other people are not. Phones, apps, and the web are so indispensable to our daily lives that we have become a captive audience. For the 15 million rides per day across 500 cities, the lack of communication between UberPool passengers may create an environment with no trust because strangers will inherently feel uncomfortable with others in such close quarters. Effectively, this lack of trust invariably leads to a safety concern. This can especially be a problem when Uber Pool is used late in the evening, while visiting a new city, or by a woman alone. Given the frequency of Uber rides per day, these scenarios are all too often; therefore, there’s an opportunity in the UberPool experience to focus on creating trust.

Competitive Audit

According to Vox, Uber currently holds 69.8% of the consumer ride-sharing market. However, emerging ride-sharing services like Alto are not only creating a new standard for on-demand rides and but also present themselves as rivals as they are bringing hospitality to ride-sharing while consistently making safety and quality its top priority. What’s more, they offer their customers more control of their experience through customization of preferences and white glove and bespoke services. Therefore, how might Uber keep its competitive edge by improving their offerings, maintaining customer satisfaction and safety, and innovate their experiences?

RESEARCH PROCESS

Research Goal

We sought out to explore how UberPool passengers would respond to quiet, neutral, and chatty environments. In order to simulate the natural occurrence of conversation, we hypothesized how we might create different scenarios for engagement between passengers. For example, assume Jacquelyn gets into an UberPool with two passengers already conversing; however, she is not let into the conversation. During a different trip, she gets into a car with two passengers already conversing, and they invite her into the conversation.

When examining our own past experiences when riding UberPool we realized that we typically fell into either of the two scenarios mentioned above-when conversations were already being had between passengers. With this understanding, we outlined the goal of our research: to discover and have passengers explain their motivations for their social atmosphere preference and their experience in that atmosphere.

Research Plan

Two different experiments were designed to simulate the two environments. In the first experiment, Ismael and I engaged with themselves. This experiment simulated the environment of a passenger getting into the car, where the other two passengers were already conversing. For the second experiment, Ismael and I engaged with the third passenger. Experiment 2 mirrored the scenario of a passenger getting into a car with two other passengers already conversing but were open to engaging with the third passenger.

Before the study, we practiced role-playing through the experiments with several friends.

For each experiment, we took 5 Uber Pool rides around Manhattan. We recorded the 10 interviews using Otter.ai, which is an iOS app that records and transcribes the conversation in real-time. This allowed us to listen together, read the transcripts, and analyze the frequency of key terms after the research study. Using this approach was instrumental in helping us design with empathy and ensuring that we kept the user's voice (literally and figuratively) throughout our design process.

Above are some of our Uber rides around Manhattan.

Ismael and I lead experiments 1 and 2, respectively. In an attempt to be as discreet as possible, we decided to forgo clipboards and notebooks. Instead, we used index cards where we wrote down our research questions for each experiment. We believe that this helped us reduce the perception from passengers that they were being conducted on. This is important because we could potentially get false-positive responses.

From left-to-right: Me conducting research in an UberPool and our experiment cards.

In the following two sections, we breakdown the process for the 2 experiments. We go into detail about each experiment’s research prompt, purpose, hypothesis, and research questions we had asked passengers.

EXPERIMENT 1

Research Prompt

Ismael and I engage with themselves to evaluate how users may react to UberPool Social.

Research Objective

To examine how a third passenger may or may not be receptive to conversing with other riders spontaneously chatting. Also helpful for revealing how chatty riders may coexist with quiet or neutral riders. Or whether having a chatty rider speaking may bother the quiet/neutral riders.

Hypothesis

There's a certain type of personality to initiate and be open to speaking with others; therefore, most introverted people will opt-out. To determine this, we survey the third passenger to evaluate the social atmosphere-regardless of the context of the conversation.

Methodology

Questions for experiment 1 were asked after we had finished conversing with the third passenger and they were approximately 8 minutes away from their drop off. We initiated the experiment immediately after entering the car.

EXPERIEMENT 2

Research Prompt

Ismael and I engage with passengers to see how they react to UberPool Social.

Research Objective

To quantify each passenger's UberPool Social experience. Rather than having Uber define that a quiet, neutral or chatty environment is, each passenger will be able to create and dynamically update their own social preference profiles.

Hypothesis

Most riders will be open to entering into the UberPool Social experience, regardless of how social they may feel.

Methodology

Questions for experiment 2 were asked before the third passenger had began their ride. We initiated the experiment after disclosing that we are university students conducting research for an Uber project as soon as they had entered the car.

research insights

Summary

After interviews with passengers, it became evident that what builds trust is having some commonality on something more personal beyond quite superficial or straightforward topics — for example, movies, hobbies, music, etc. Since as our aim is to build trust among passengers through fostering connections, opening up some dialogue through a profile may be useful to build those connections that will lead to a sense of trust between the passengers. We learned that some questions that are more personal while making a great conversation starter are places traveled, languages are spoken, hometown, how they ended up in the city, etc.

Detailed Findings

DESIGN OBJECTIVE

Design to Solve the Problem, Not to Provide a Prescription to the Problem

In the following redesign, I primarily focus on the user experience design and the research process of the UberPool experience. My redesign does not consist of creating any new standalone features since I do not have access to any user research or other quantitative data from Uber. Although I do propose an additional option for UberPool, our team conducted user research on our design assumptions by prototyping our new experience in real UberPools in Manhattan.

By deciding to focus on the user experience and research portion of the design process with real users, we ensured to reinforce and enhance each design decision with a human-centered design approach. We prototyped each step of the flow with users, kept them at the center of our redesign, and incorporated their feedback and insights throughout our iterations with the sole focus of improving the user experience in UberPools.

DESIGN PROCESS

Exploratory Sketches

An intriguing fact about Uber is that people use it for a specific need and put it away, whereas other apps have their users live in them. This means that users have a very short lifecycle when using the app and that each touchpoint is very critical if passengers are prompted to do any actions.

Therefore, to start the exploration process, I thought about where in the Uber experience, there is an opportunity for passengers to interact with UberPool Social. Effectively, there are two instances: the moment before a user gets on the car while requesting a ride, and then after the user has had their ride fulfilled. Realizing this, not only have we explored multiple sketch solutions, but we’ve also mapped out their information diagrams to understand what our designs were doing beyond the pixels.

Filling in the Social Profile

Proposition 1

From left-to-right: User flow sketches and information flow for Proposition 1.

Above are a series of screens that outline the user flow before a passenger would get into their UberPool. The flow captures the moment from when the passenger chooses their ride option to when the passenger gets on the car and is traveling to their destination. I drew a user flow of the experience and identified areas where passengers could begin to interact with UberPool Social. Within this flow, we needed passengers to be able to (1) choose their preferred social atmosphere, (2) fill out their social profile and (3) view the co-rider’s social preference as well as some starter questions generated from the matched profile.

To the right of the user flow sketch, we detailed the information architecture into a logic diagram. The purpose of doing this was to make sure that we were not adding any friction (such as conditionals and complex/unnecessary decision points) within the experience. This helped us reveal whether our design decisions may actually be creating bottlenecks in the flow.

Proposition 2

From left-to-right: User flow sketches and information flow for Proposition 2.

As identified above, one of the three key interactions with UberPool Social is when the users fill out their social profile. However, by prompting the users to fill out their social profile while waiting for their ride to be confirmed and driver to arrive, we realized that the users may experience friction as well as cognitive overload. Furthermore, we saw a potential problem of users not having enough time filling in their profile while waiting for the driver to arrive, as the waiting time varies in each ride request. That is initially why we gave the users the option to fill in their profile even while in the car, but this would lead to two more potential problems: (a) the users may wonder about the use of their data inputted, as the car will be on its way to pick up the next co-rider already (or even have a co-rider prior to their pickup) and yet they are asked to fill out information in order to better match them with a co-rider; (b) it would defeat the purpose of encouraging a conversation if we prompt the users to interact with the app, filling in their profiles, as opposed to interacting with the other passenger.

Even when the user successfully fills out their profile before their car arrives, it is such a short turnaround time between the moment they fill in the profile and the moment the car arrives, which would be confusing for the users. Thus, we decided there must be a better time to ask for the users to fill out their profile.

As mentioned before, we identified the two key touchpoint opportunities for the users to interact with UberPool Social to be (1) before their car arrives and (2) after the ride is completed. Thus, we devised a second proposition wherein the user would be asked to fill out their profile once the ride is completed.

As shown above, we have this time divided the user flow into two different scenarios: first time users, and second+ time users. As captured in the sketches above, the first time users will be given generic conversation starters during their ride, and only after the ride is fulfilled, they will be given the option to edit their social profile. If the user decides to fill out their social profile after the ride, in their next rides, they will have a customized set of conversation starter questions that are tailored towards their specific profile. Should the user skip the option to fill out their profile, they will be asked to fill out their profile after the completion of the next two future rides, and on the third time they decline to fill out the profile, they will be reminded that they can always fill out their social profile on the settings page and will not be asked again.

Proposition 3 (Final Wireframe)

From left-to-right: User flow sketches and information flow for Proposition 3.

Based on the findings from our user testing, we were able to sketch out the final design decisions as displayed above. Notably, the biggest difference was the position of the social profile settings. In the following section, I discuss the user insights and feedback that informed our design decisions and reason for choosing proposition 3.

Social Experience Rating

When exploring where passengers would interact with the UberPool Social, I realized that there was a touchpoint opportunity when they would be required to rate the driver. Below is my process involving four design iterations in the form of propositions. Within each one, their sketch followed by a brief explanation of their respective trade-offs are outlined.

Proposition 1

Initially, the rating of the social experience lived on the same screen as the driver rating. Notably, it was placed below the section that a passenger would tip a driver. I brainstormed how the social atmosphere rating data could be quantified and used in interesting ways. Logically, I realized that it might be confusing for users to interact with a Likert scale with increasingly negative responses, which would be used to rate a bad social experience.

Proposition 2

Rather than using a Likert scale with increasingly negative responses, I explored how passengers may provide qualitative feedback regarding their social experience. The qualitative feedback provided to drivers inspired this design decision. Although this may be useful in understanding how passengers may receive UberPool Social, it does not necessarily help with making the social experience better. Namely, because those three passengers are most likely to never be in a car again together; therefore, there is no attempt at improving the social atmosphere. Whereas qualitative feedback is helpful for drivers because they can use it to improve their service.

Proposition 3

I realized that having passengers rate the social experience on the same screen as they would rate the driver may create cognitive overload and thus confusion. The rating experience here is actually split up into two screens (1) rating for the driver and (2) rating for the social atmosphere. In order to make sure that the passenger knew which rating corresponded to the correct context, an additional screen is added; therefore, creating a two-screen navigation stack.

Proposition 4 (Final Wireframe)

Here, I followed the same approach of splitting the driver and social atmosphere rating. Furthermore, I wondered if it was necessary to ask for detailed feedback if they thought the social atmosphere was good. On the contrary, if their experience was bad, then it would be necessary to gather more information regarding that bad experience.

While exploring this proposition, I questioned whether or not Uber should define the atmosphere for quiet, neutral, and happy to chat rather than allowing passengers to create their own preference for the atmospheres mentioned above. Namely, would it be possible for passengers to fine-tune their atmosphere preferences if and only if they had a bad experience? In the hi-fidelity design, I explain my thinking, reasoning, and design decisions for why proposition 4 was chosen.

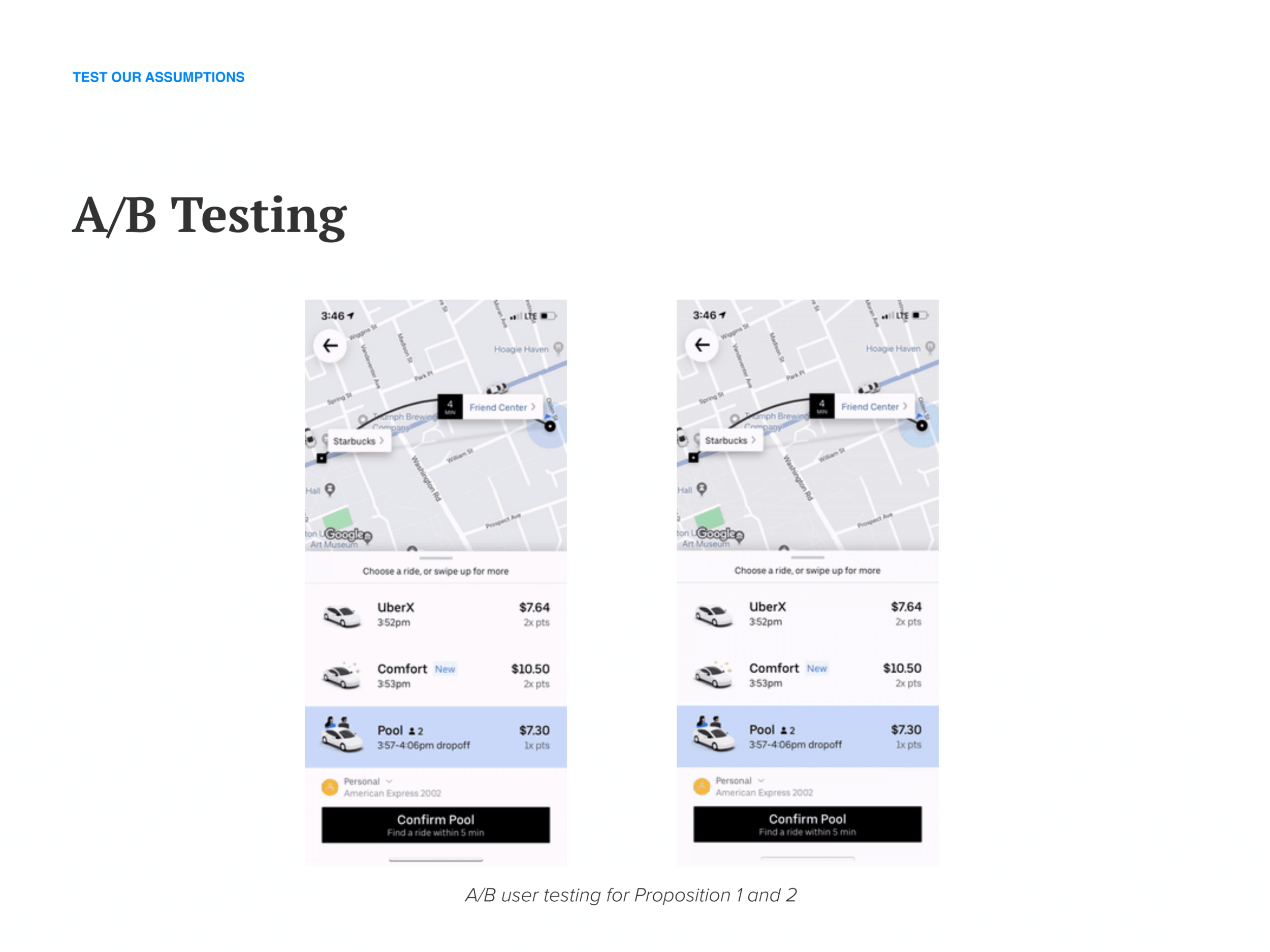

a/b testing our social profile fill-in assumptions

Talk Out Loud User Testing Walk-Throughs

After designing two different propositions (proposition 1 and proposition 2) for the social profile completion touchpoint, we decided to test our assumptions. We conducted research and got real feedback from 5 Uber users to help us determine which flow was more seamless and intuitive. These insights informed our final design decisions for proposition 3. During the study, I had each user think out loud that they were experiencing as they interacted with the app.

One of the key insights is that the user does not look at the Uber app after they request a ride. One of the users mentioned that he is always either “lost, late, or chasing after [his] driver.” In other words, he rarely interacts with the Uber app once the ride is confirmed, and the driver is on his way because he needs to run to the pickup location. He mentioned that most of the time he requests an Uber, he calculates the time it would take the driver to arrive, and then finishes up preparing to leave his house or leave the restaurant. Therefore, inserting the “social profile fill in” while the driver is arriving will not be a meaningful touchpoint. This confirms the idea that inserting the social profile interface once the ride is completed would be a better opportunity to prompt.

Another user mentioned that while he does look at his screen to wait for a ride to be confirmed and driver to be assigned, he would not have the bandwidth to fill out a social profile during his wait. The user highlighted that it is because he would be too occupied waiting for a ride to be confirmed, especially since he is usually also busy searching for a ride in other car-sharing apps such as Lyft and Via simultaneously. He mentioned that he would be “distracted from the real priority—the more important task” (ordering a ride). These insights confirmed our assumption that in theory, it might be a clever use of time to utilize the timeframe of the user waiting for a ride to be confirmed and for the driver to arrive as an opportunity to fill out the profile, in reality, there is much more going on around their circumstances. In other words, most users do not use the app from the moment they confirm the pickup location. Furthermore, the user pointed out that since he would stop the interaction with the app once the ride is confirmed, he would be even further away from looking at the app once he is in the car. This signified that having the general conversation starter questions live in the user flow of after getting on the car would be difficult for it to be even noticed of its existence, let alone actually utilized. Therefore, this provided us an insight that there must be a better point to introduce the generic conversation starters, or at least hint at the user that it is there.

From left-to-right: A/B user testing for proposition 1 and 2.

Then, naturally, I was curious to see what the users thought of the second proposition, where we inserted the profile fill in after the ride’s completion. Mainly, the question we had was: ‘would the users be interested in filling out the profile?’ as this was the concern that drove us to locate the profile completion when they are (in theory) required to look at the app (which was disproved above). One user highlighted that looking at how the buttons are positioned (how the “Edit Social Profile” button is “glaring at [him]”), he would be compelled to fill out the user profile, as it would look like “unfinished business” otherwise. He pointed out that he does not want to leave anything unfinished; if it is there, he would do it. He said, “it would take a minute. I’ll just do it.” However, when I asked if he would still fill out the profile when the “No” button were positioned side by side with the “Edit Social Profile” button, he mentioned that he would most likely not fill it out. Therefore, this valuable insight guided us to decide how to position the profile editing button.

When I asked specifically about the “Edit Social Profile” page, one user pointed out that she would love to fill it out if they were drop down options, as it is easier to fill in. She said that she wouldn’t want to type the answers manually. When I asked which questions she would answer and which ones she would leave blank, she mentioned that she would answer all of the ones that could be easily filled out (Favorite Cities, Hometown, Languages, Travel Wish List, Favorite Book, and Favorite Artist), but not “Can’t Stop Talking About” as she’d have to type a topic in. This provided an insight of how the social profile questionnaires should require minimum effort, and make it so easy so that they would not want to skip it.

Most importantly, the users loved the social experience preference setting - one of the users said he was surprised it is not already within the Uber app, as it seemed like a “no brainer” to have that option for him.

HIGH-FIDELITY DESIGNS

Below are the final design mockups for both the experience of filling out the social profile and rating the social atmosphere. Each screen within the flow is detailed with its respective steps. Moreover, there is blue text and call-out cards which indicate my proposed design decisions within the ecosystem of Uber within the following two sections.

Filling in the Social Profile

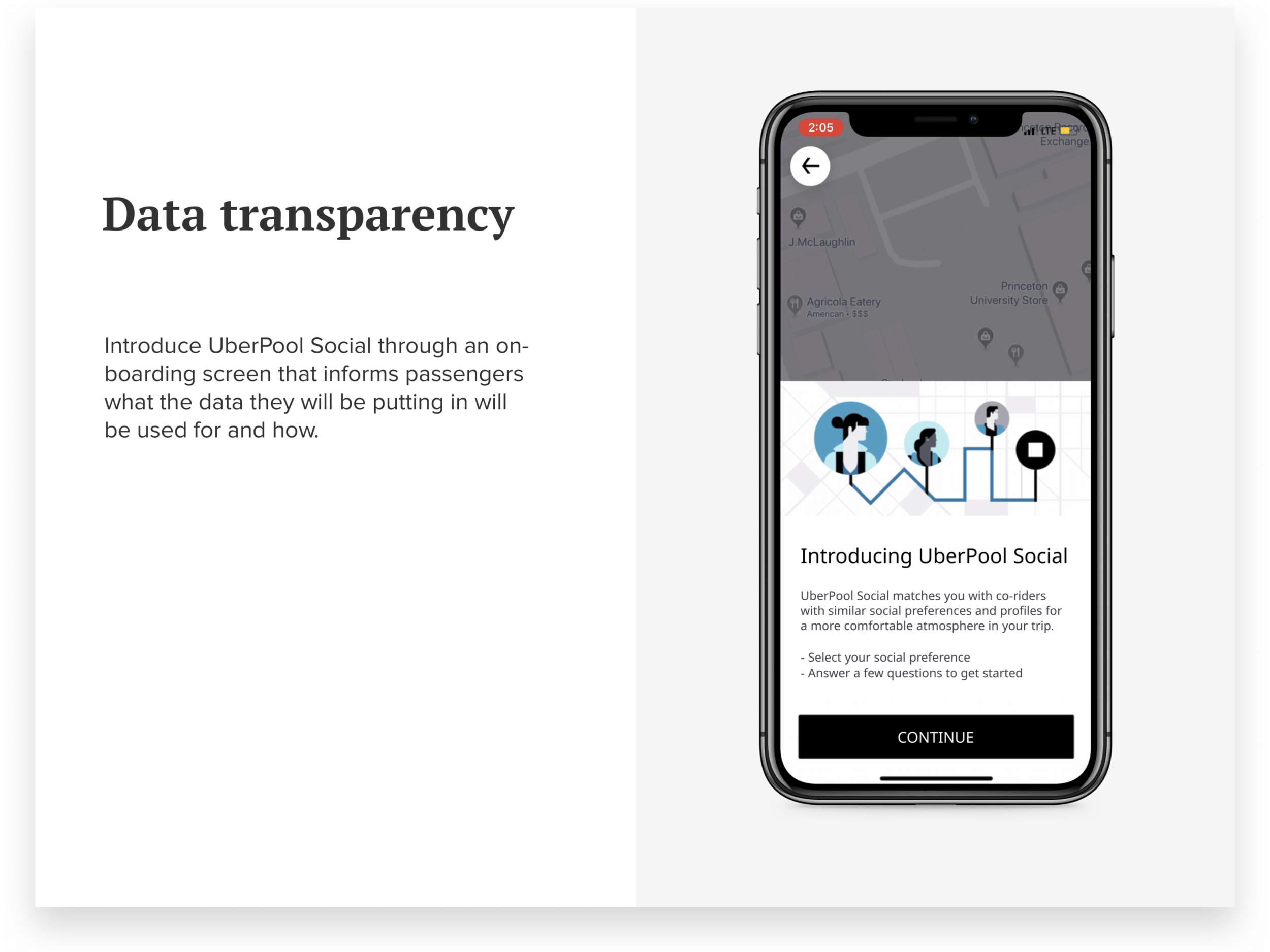

It's important to note that this flow is only for people who are new to UberPool Social. Passengers who have already filled out their profiles will be able to update them from the "Settings" section from the hamburger menu.

Let us explore the flow for UberPool Social from left-to-right. The first and second step has the user open the Uber app and request an UberPool, respectively. Next, the user confirms their pickup location as usual. During the fourth step, we found an opportunity to redesign the original UberPool introduction screen to explain to passengers what UberPool Social was. Interestingly enough, Uber had screen in this step that introduced what UberPool was; however, we used this as an opportunity to change the copy to introduce UberPool Social. Most importantly, we were mindful of our copy as we made it clear why we were using people's information and what it would be used for. We inform the passenger that they will have the opportunity to fill out several questions on the upcoming screens.

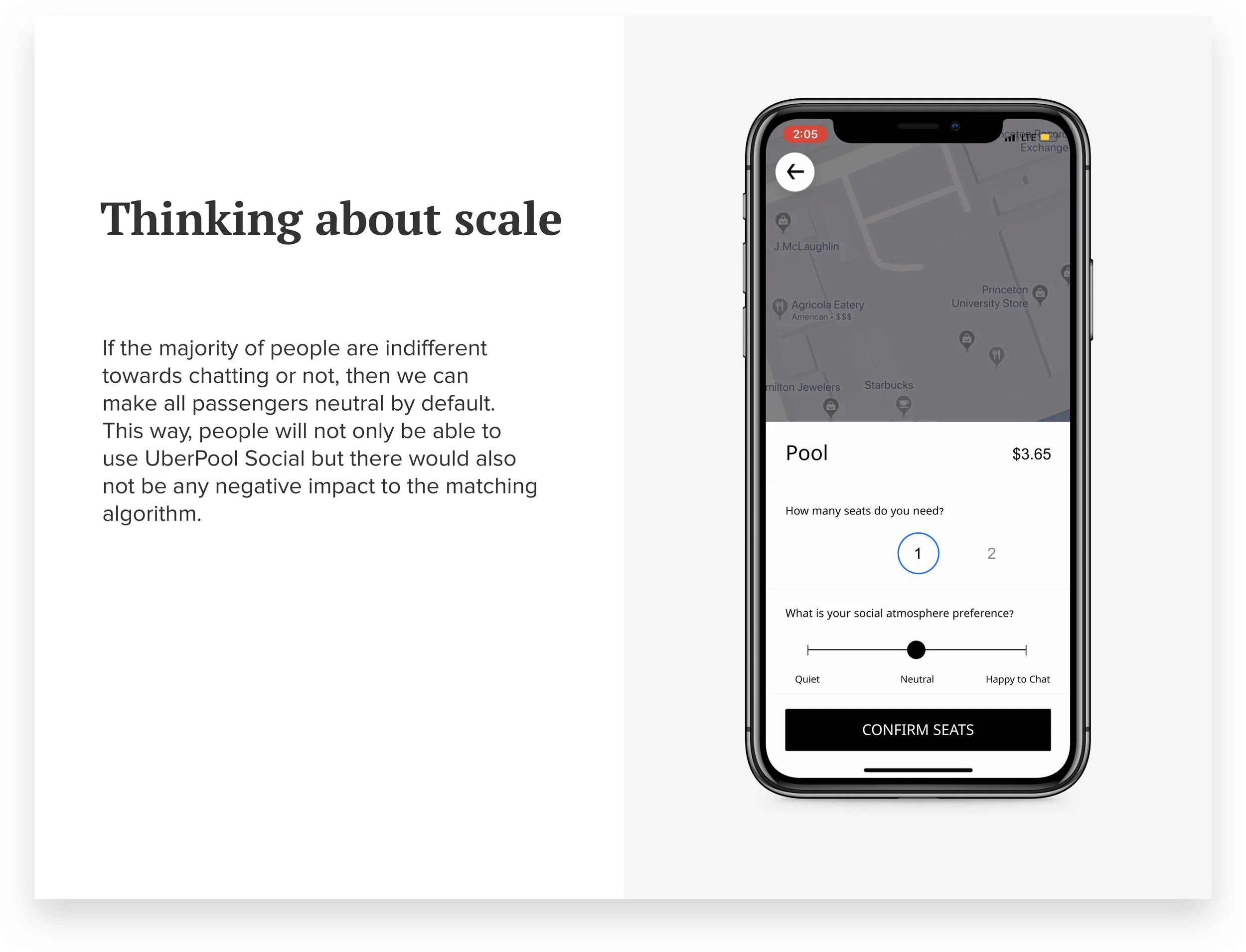

On step five, passengers have the choice to choose their social atmosphere preference in addition to the number of seats they may need. By default, the slider will be at the neutral option for everyone at the beginning of each ride. From our user research, we learned that passengers were more or less willing to chat if the opportunity or the environment prompted it. This was a surprising discovery because we realized that we could, in fact, match quiet and neutral individuals since they could comfortably co-exist in the same social atmosphere. Therefore, no negative ramifications would occur to the UberPool algorithm for matching passengers with other passengers. This is a significant concern for Srikanth because he heavily questioned us on how UberPool Social would scale.

During step 6, Uber will confirm the request, and on step 7, the passenger will wait to be matched with a driver. During step 8, the passenger will have a driver assigned. What’s more, sample conversation starter questions will be available for the passenger before and during the ride. Most interestingly, these retracted modal cards transition themselves into a full screen expanded view; however, its functionality and content remain. Therefore, the design will be able to work because (1) passengers are used to seeing this change, and (2) all the information gets translated correctly.

Steps 9a and 9b show different sample conversation starter questions depending on whether or not the passenger has completed their social profile. Note, the degree of personalized questions in 9b as the co-rider has completed their profile. On step 10, the passenger will still have the option to rate their driver as usual. Finally, on step 11, there would be a prompt for the passenger to complete their social profile (if they haven’t done so already). The passenger has the option to opt-out by choosing the “skip“ option, and in this case they would continue to use UberPool Social but with general questions.

However, passengers who complete their profile in this step, will have more personalized questions the next time they use UberPool Social, and in this screen they’d have the option rate the social experience. We discuss this flow in the next section.

Social Experience Rating

In the above redesign, the rating experience is split up into two screens (1) rating for the driver and (2) rating for the social atmosphere. The purpose of this design decision was to have passengers know which rating corresponded to the correct context. Effectively, this creates a 2-screen navigation stack. This design decision follows the same design pattern and convention as the rating flow (for couriers and restaurants) from UberEats.

From left-to-right: UberEats review flow and my redesign for the new rating flow with the social atmosphere rating (prototyped in Marvel).

Similarly to the UberEats rating experience, passengers still have the option to skip the rating or move through the navigation stack. In the gifs below, I present an example of UberEat’s review flow and how I followed the same design language, making sure to adhere to the Uber design ecosystem.

From our user research, we learned that neutral and chatty people are fluid in quiet or chatty environments. Namely, they are indifferent towards either talking or not. Therefore, if a passenger selects either a neutral or chatty environment, they will not have to rate it. However, if a passenger chooses a quiet, they have the option to rate the social atmosphere. If they enjoyed the environment and give a thumbs up, then they are good to go. If they did not enjoy the environment, then we have the opportunity to learn how it affected it. This is critical because passengers have agency over how they define their own quiet atmosphere rather than having Uber defining a "general quiet atmosphere."

This is particularly important for people like the Realtor (from experiment 1) who had stated that "If [he does not] feel like talking in the car, [he] would be comfortable with others talking." He goes on to explain that he would be more than happy to engage with them if he wanted to. Being sure that our design addresses the needs of passengers who want a specific type of quiet atmosphere was a consideration that Srikanth had brought up, and we believe that our design offers a solution to his feedback.

RECAP

Confronting our Assumptions

Thinking About Scalability

When proposing a new option in an already existing ecosystem where nearly 4 million Uber trips happen every day in the US-that's more than 45 rides every second, issues around scalability should always be considered. Srikanth had asked us, "How will our proposition affect the Uber algorithm? Will people have to wait longer to be matched accordingly?" Below, we list our assumptions as well as our reasoning around them.

Our approach to this challenge was the following. To make the default social atmosphere option to be neutral for each passenger before every UberPool Social trip. We believed that passengers would almost always choose this option when booking a ride. We arrived at this assumption because from user research; most participants felt neutral about engaging in conversation. However, our presence as researchers (Ji Yeon and I) may have caused a false-positive. We do not know how people would respond if they had to make the option in the app.

However, if the majority of people were neutral, we would not only allow people to experience UberPool, but we also will not negatively impact the matching algorithm. For example, if neutral people are indifferent towards either talking or not in both quiet and chatty environments, then we could match quiet-neutral, neutral-neutral, and neutral-chatty. Namely, the algorithm would have a more substantial subset of people to match; therefore, wait times would not be significantly longer.

Finally, to protect against the case that we cannot match a passenger in a preferred social atmosphere, Uber would be transparent about not being able to make a match and that we can put them in a different atmosphere to save time.

How Will the Social Rating Scale?

We assumed that passengers would need to rate a quiet social atmosphere and not neutral or chatty. The reasoning behind this design decision was because passengers have expectations for a quiet ride. Effectively, there's more of a disappointment to get into a car expecting it to be quiet, and it's not compared to getting into a car expecting it to be chatty, and it's not.

Now, if a passenger had a negative experience in a quiet car, and they wanted it to be quieter, we would take that feedback and build a social preference profile for how they define a quiet environment. This would help us match them with other co-riders who have similar tolerances for quiet-only when the quiet option is chosen.

Revisiting Feedback from Srikanth and Judges

It's important to note that my redesign does not add any new standalone features; instead, it proposes an additional option to UberPool. More specifically, it allows for the increased in social interactions among co-riders with the byproduct being increased perceived comfort, trust, and safety. Below, I address our approach to Srikanth’s and the Judge’s feedback.

1. How will you incorporate UberPool Social at scale while maintaining safety and trust?

2. How will our proposition affect the Uber algorithm? Will people have to wait longer to be matched accordingly?

3. Does this experience improve trust or safety in the car?

CONCLUSION

Reflections, Results, and Key Takeaways

Admittedly, Uber has taken initiative towards addressing trust and safety concerns. However, no action has been taken for Uber services between multiple passengers (e.g., UberPool). UberPool Social offers an approach to helping increase social interaction with the byproduct being increased perceived comfort, trust, and safety.

However, without having any research, data, or access to Uber's engineering, design, and business teams, it is difficult to evaluate how our proposed design decisions may reveal how passengers receive UberPool Social and its effect on the UberPool algorithm.

Most importantly, I learned the importance of designing within an existing product ecosystem. Namely, designing to introduce how UberPool Social may fit into the wider Uber passenger experience and understanding how this new option may fit into the more expansive Uber product canvas. For example, the key question at stake was whether or not people were interested in the social experience preference feature, giving them the agency to control the social atmosphere in the car to their needs. The majority of the users loved the social experience preference setting-one of them said he was surprised it is not already within the Uber app, as it seemed like a “no-brainer” to have that option for him. Keeping in mind how our new feature would live within the overall Uber ecosystem, I scrutinized my design decisions by questioning how it would fit under the Uber ecosystem. For example, “in an ideal world, how would this fit to the Uber ecosystem? How would you expect these social features to come up in Uber X, Uber XL, etc.?”

Now, Uber released Uber Comfort in select cities. This option allows passengers to control the quietness level and HVAC climate control. Interestingly, the user we studied, mentioned that it is a “no-brainer” to have the option to control the quietness level further added on, saying that this feature can reside in all other types of Uber rides, and in fact, should exist. He said that having a catered social atmosphere should not be a privilege. The user said that “it does not make any sense to pay for someone to not distract you as Uber Comfort does.” This insight was constructive in not only revealing that the new feature strikes as a useful feature to the current Uber users, but also that there is potential for the feature to extend beyond Uber Pool.

What I Learned

Researching emerging ride-sharing services in the market, learning about their competitive edge, as well as their disadvantages, and exploring ways Uber can innovate within and around their products and services.

Intensive background research in areas I’m not familiar with. Particularly around safety reports and guidelines, and news publications.

Conducting several rounds of qualitative user research in time-sensitive environments. Mike Tyson says, "everyone has a plan until they get punched." That could not be any more than true. Before conducting the 6 rounds of research, we had struggled with 3 rounds before--even after role-playing with friends. The uncertainties, ambiguities, and challenges of being out in the field are nothing you can truly prepare for, and the best you can do is to improvise.

Many digital experiences can quickly be prototyped in a very low-fidelity way. For example, our final deliverable for Rehack was a high-fidelity mockup, which in theory could have been tested quickly without going to such lengths. The experience of doing both parts 1 and 2 has shown me how to move fast as a designer as this is necessary when working on teams, deadlines, and at companies where the stakes are higher.

Designing for a product that has a low lifecycle for a user—this is not Instagram. Uber is used to order a ride. You take out your phone make a request leave the app, come back when the driver is almost near, and when you get into the car, you will most likely not return back to the app. Learning how to optimize any opportunity for when the user interacts with the product can be challenging and limiting.

Looking Forward

What I would test next: During the exploratory phase, for “After the ride: Social rating,“ I brainstormed proposition 3 which provided qualitative feedback regarding the rating of the social atmosphere. It would be interesting to open up UberPool Social to a subset of users and investigate feedback from passengers who chose a certain social atmosphere preference and rated that atmosphere after the ride. The value in this that we get honest insights regarding how people feel in the car and what they think about UberPool Social.

How it will live within the Uber Ecosystem: During the user testing, I have asked our users questions that provide insights as to how this feature may be extended beyond Uber Pool and further into other options such as Uber X, Uber XL, Uber Black, and so on. Most users responded that this feature of allowing to control the social atmosphere of the car, whether it is between the passengers or between the driver and the passenger, is an extremely useful feature that should be there regardless of the category. As a next step, I would very curious to see how this feature may fit into other ride options within the Uber ecosystem, and design different ways to fine tune the social atmosphere of a private ride, between the passenger and the driver.

Engage in different geographical locations to identify gaps: All of our user research was done in Manhattan. We had the luxury of dense city with numerous UberPool requests and low wait times. However, how would UberPool Social work in other cities that are not as dense? How would UberPool Social affect wait times? I’m interested in understanding the dynamics and factors that go into the UberPool algorithm to better understand if there is an opportunity to fine-tune UberPool Social for different geographical locations.

Design. Build. Test. Learn. Repeat.: During the redesign, we did many explorations. In fact, we drew out information diagrams to understand what our designs were doing beyond the pixels. We did my best to constrain my design decisions around what I would think would be real-life constraints at Uber. The purpose was to prevent myself from being romantic and falling in love with my designs. Effectively, I became more critical of myself. In the real-world, how would my redesign do with constraints and objectives from the engineering team?